| |

|

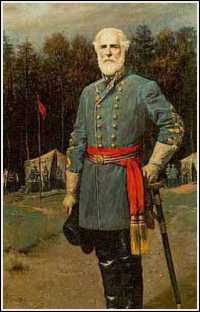

Page 2 It will be understood by all who read any biographical

sketch of one so eminent as the Southern military leader thus

portrayed in Mr. Hill's splendid words, that the facts of his life must sustain the eulogy.

Fortunately this support appears even in the cold recital which is

here attempted. General Lee was born at Stratford, Virginia, January

19, 1807, and was eleven years old on the death of his chivalric

father, General Henry Lee, the "Light Horse Harry" of the American

revolution. In boyhood he was taught in the schools of Alexandria,

chiefly by Mr. William B. Leary, an Irishman, and prepared for West

Point by Mr. Benjamin Hallowel1. He entered the National military

academy in 1825, and was graduated in 1829, without a demerit and

with second honors. During these youthful years he was remarkable in

personal appearance, possessing a handsome face and superb figure,

and a manner that charmed by cordiality and won respect by dignity.

He was thoroughly moral, free from the vices, and while "full of

life and fun, animated, bright and charming," as a contemporary

describes him, he was more inclined to serious than to gay society.

splendid words, that the facts of his life must sustain the eulogy.

Fortunately this support appears even in the cold recital which is

here attempted. General Lee was born at Stratford, Virginia, January

19, 1807, and was eleven years old on the death of his chivalric

father, General Henry Lee, the "Light Horse Harry" of the American

revolution. In boyhood he was taught in the schools of Alexandria,

chiefly by Mr. William B. Leary, an Irishman, and prepared for West

Point by Mr. Benjamin Hallowel1. He entered the National military

academy in 1825, and was graduated in 1829, without a demerit and

with second honors. During these youthful years he was remarkable in

personal appearance, possessing a handsome face and superb figure,

and a manner that charmed by cordiality and won respect by dignity.

He was thoroughly moral, free from the vices, and while "full of

life and fun, animated, bright and charming," as a contemporary

describes him, he was more inclined to serious than to gay society.

He married Mary Custis, daughter of Washington Parke

Custis, and grand-daughter of Martha Washington, at Arlington,

Va., June 30, 1831. Their children were G. W. Custis, Mary, W.

H. Fitzhugh, Annie, Agnes, Robert and Mildred.

At his graduation he was appointed second-lieutenant of

engineers and by assignment engaged in engineering at Old Point

and on the coasts. In 1834 he was assistant to the chief

engineer at Washington; in 1835 on the commission to mark the

boundary line between Ohio and Michigan; in 1836 promoted first

lieutenant, and in 1838, captain of engineers. In 1837 he was

ordered to the Mississippi river, in association with Lieutenant

Meigs (afterward general) to make special surveys and plans for

improvements of navigation; in 1840 a military engineer; in 1842

stationed at Fort Hamilton, New York; and in 1844 one of the

board of visitors at West Point. Captain Lee was with General

Wool in the beginning of the Mexican war, and at the special

request of General Scott was assigned to the personal staff of

that commander. When Scott landed 12,000 men south of Vera Cruz,

Captain Lee established the batteries which were so effective in

compelling the surrender of the city. The advance which followed

met with serious resistance from Santa Anna at Cerro Gordo. Here

Captain Lee made the reconnaissances and in three days' time

placed batteries in positions which Santa Anna had judged

inaccessible, enabling Scott to carry the heights and rout the

enemy. In his report Scott wrote: "I am compelled to make

special mention of Captain R. E. Lee," and the brevet as major

was accorded the skillful artilleryman. The valley of Mexico was

the scene of the next military operations, and here Lee

continued to serve with signal ability and personal bravery. One

act of daring General Scott afterward referred to as" the

greatest feat of physical and moral courage performed by any

individual in my knowledge pending the campaign." Having

participated in the daylight assault which carried the

entrenchments of Contreras, Captain Lee was soon afterward

engaged in the battles of Churubusco and Molino del Rey, gaining

promotion to brevet lieutenant-colonel. In the storming at

Chapultepec, one of the most brilliant affairs of the war, he

was severely wounded, and won from General Scott, in his

official report, appreciative mention as being "as distinguished

for execution as for science and daring." After Chapultepec he

was recommended for the rank of colonel. The City of Mexico was

next taken and the war ended.

Among the officers with Lee in Mexico were Grant, Meade,

McClellan, Hancock, Sedgwick, Hooker, Burnside, Thomas,

McDowell, A. S. Johnston, Beauregard, T. J. Jackson, Longstreet,

Loring, Hunt, Magruder, and Wilcox, all of whom seemed to have

felt for him a strong attachment. Reverdy Johnson said he had

heard General Scott more than once say that his "success in

Mexico was largely due to the skill, valor and undaunted energy

of Robert E. Lee." Jefferson Davis, in a public address at the

Lee memorial meeting November 3, 1870, said: "He came from

Mexico crowned with honors, covered with brevets, and

recognized, young as he was, as one of the ablest of his

country's soldiers." General Scott said with emphasis: "Lee is

the greatest military genius in America." Every general officer

with whom he personally served in Mexico made special mention of

him in official reports. General Persifer Smith wrote: "I wish

to record particularly my admiration of the conduct of Captain

Lee, of the engineers--the soundness of his judgment and his

personal daring being equally conspicuous." General Shields

referred to him as one" in whose skill and judgment I had the

utmost confidence." General Twiggs declared" his gallantry and

good conduct deserve the highest praise," and Colonel Riley bore

"testimony to the intrepid coolness and gallantry exhibited by

Captain Lee when conducting the advance of my brigade under the

heavy flank fire of the enemy."

In the subsequent years of peace Lee was assigned first

to important duties in the corps of military engineers with

headquarters at Baltimore, from 1849 to 1852, and then served as

superintendent of the military academy at West Point until 1855,

when he was promoted brevet lieutenant-colonel and assigned to

the Second cavalry, commanded by Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston

This remarkably fine regiment included among its officers

besides Johnston and Lee, Hardee, Thomas, VanDorn, Fitz Lee,

Kirby Smith, and Stoneman, later distinguished in the

Confederate war. With this regiment Lee shared the hardships of

frontier duty, defending the western frontier of Texas against

hostile Indians from 1856 until the spring of 1861. In October,

1859, he was at Washington in obedience to command, and

fortunately so, as during his visit occurred the John Brown

raid. President Buchanan selected him to suppress the movement,

which he did with prompt vigor, after giving the proper summons

to Brown to surrender. Returning to Texas, he was in command of

the department in 1860 and early in 1861, while the Southern

States were passing ordinances of secession, and with sincere

pain observed the progress of dissolution. Writing January 23,

1861, he said that the South had been aggrieved by the acts of

the North, and that he felt the aggression and was willing to

take every proper step for redress. But he anticipated no

greater calamity than a dissolution of the Union and would

sacrifice everything but honor for its preservation. He termed

secession a revolution, but said that a Union that can only be

maintained by swords and bayonets had no charms for him. "If the

Union is dissolved and the government disrupted, I shall return

to my native State and share the miseries of my people; and save

in defense will draw my sword on none."

About a month later Lee was summoned to Washington to

report to General Scott and reached the capital on the 1st of

March, only a few days before the inauguration of Lincoln. He

was then just fifty-four years of age, and dating from his

cadetship at West Point had been in the military service of the

government about thirty-six years. He had reached the exact

prime of maturity; in form, features, and general bearing the

type of magnificent manhood; educated to thoroughness;

cultivated by extensive reading, wide experience, and contact

with the great men of the period; with a dauntless bravery

tested and improved by military perils in many battles; his

skill in war recognized as of the highest order by comrades and

commanders; and withal a patriot in whom there was no guile and

a man without reproach. Bearing this record and character, Lee

appeared at the capital of the country he loved, hoping that

wisdom in its counsels would avert coercion and that this policy

would lead to reunion. Above all others he was the choice of

General Scott for the command of the United States army; and the

aged hero seems to have earnestly urged the supreme command upon

him. Francis P. Blair also invited him to a conference and said,

"I come to you on the part of President Lincoln to ask whether

any inducement that he can offer will prevail on you to take

command of the Union army." To this alluring offer Lee at once

replied courteously but candidly that though "opposed to

secession and deprecating war he would take no part in the

invasion of the Southern States." His resignation followed at

once, and repairing to Virginia, he placed his stainless sword

at the service of his imperiled State and accepted the command

of her military forces. The commission was presented to him in

the presence of the Virginia convention on April 23, 1861, by

Mr. Janney, the president of that body, with ceremonies of great

impressiveness, and General Lee entered at once upon duties

which absorbed his thought and engaged his heart. The position

thus assigned confined him at first to a narrowed area, but he

diligently organized the military strength of Virginia and

surveyed the field over which he foresaw the battles for the

Confederacy would be fought. As late as April 25 he wrote, "No

earthly act would give me so much pleasure as to restore peace

to my country, but I fear it is now out of the power of man, and

in God alone must be our trust. I think our policy should be

purely on the defensive, to resist aggression and allow time to

allay the passions and permit reason to resume her sway."

Back to page one

Continued on page three |

|

|

splendid words, that the facts of his life must sustain the eulogy.

Fortunately this support appears even in the cold recital which is

here attempted. General Lee was born at Stratford, Virginia, January

19, 1807, and was eleven years old on the death of his chivalric

father, General Henry Lee, the "Light Horse Harry" of the American

revolution. In boyhood he was taught in the schools of Alexandria,

chiefly by Mr. William B. Leary, an Irishman, and prepared for West

Point by Mr. Benjamin Hallowel1. He entered the National military

academy in 1825, and was graduated in 1829, without a demerit and

with second honors. During these youthful years he was remarkable in

personal appearance, possessing a handsome face and superb figure,

and a manner that charmed by cordiality and won respect by dignity.

He was thoroughly moral, free from the vices, and while "full of

life and fun, animated, bright and charming," as a contemporary

describes him, he was more inclined to serious than to gay society.

splendid words, that the facts of his life must sustain the eulogy.

Fortunately this support appears even in the cold recital which is

here attempted. General Lee was born at Stratford, Virginia, January

19, 1807, and was eleven years old on the death of his chivalric

father, General Henry Lee, the "Light Horse Harry" of the American

revolution. In boyhood he was taught in the schools of Alexandria,

chiefly by Mr. William B. Leary, an Irishman, and prepared for West

Point by Mr. Benjamin Hallowel1. He entered the National military

academy in 1825, and was graduated in 1829, without a demerit and

with second honors. During these youthful years he was remarkable in

personal appearance, possessing a handsome face and superb figure,

and a manner that charmed by cordiality and won respect by dignity.

He was thoroughly moral, free from the vices, and while "full of

life and fun, animated, bright and charming," as a contemporary

describes him, he was more inclined to serious than to gay society.